‘In The Flat Field’ (8-24 August) was a collaborative exhibition by Tom Isaacs and Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa at Chrissie Cotter Gallery, inspired by the novel Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions by Edwin A. Abbott–a satire set in a two-dimensional world populated by geometric figures. The exhibition includes 2, 3, and 4D artworks exploring speculative connections between Modern art, science and mathematics, and science fiction.

‘In the Flat Field’ was supported by the Inner West Council.

Photographs by Alex Wisser and Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa.

Exhibition Layout

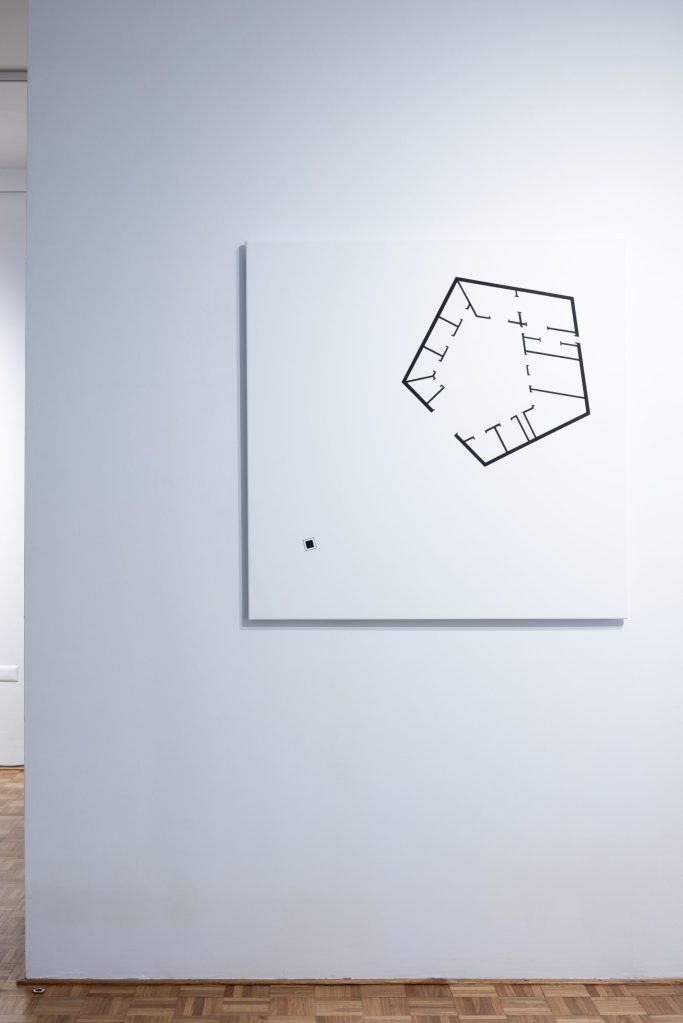

Throughout Exhibition

1. Father and Son, 2024 (ongoing).

Installation consisting of pentagons and squares distributed throughout the galleries. Vinyl emulsion on vinyl fabric.

Upstairs Gallery Area

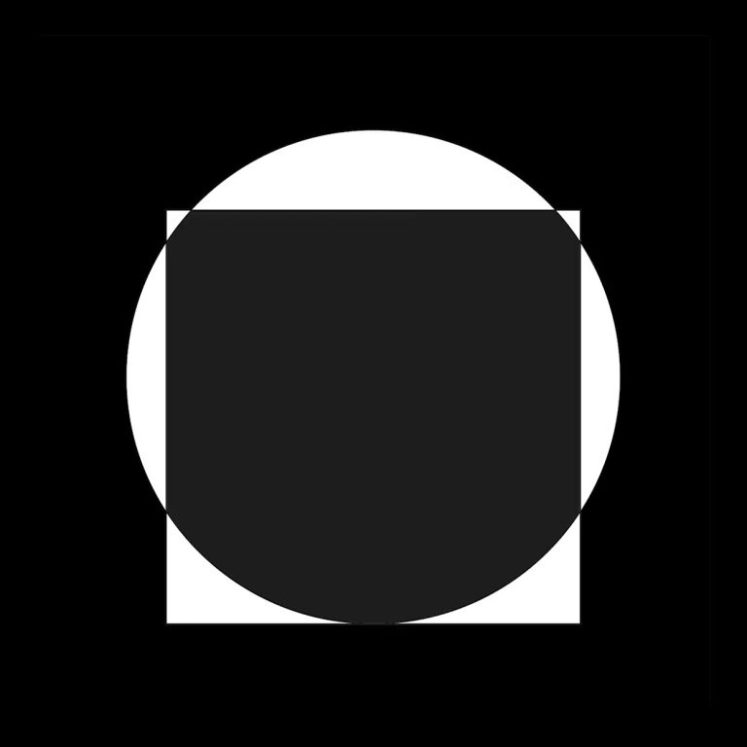

2. Vitruvian Ghost, 2024.

Single-channel projection. Digital video, 5 min, loop.

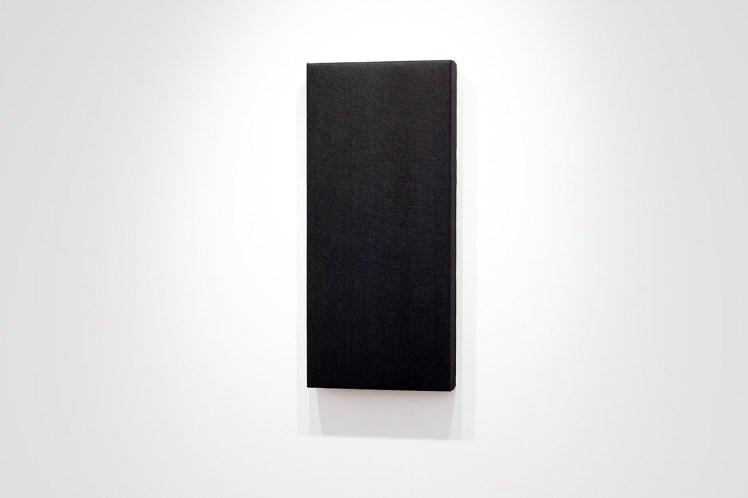

3. Monolith/Messenger, 2024.

Felt, wooden stretcher frame.

4. Neotherapeutic Operation (First Attempt), 2024.

Installation, video documentation of live performance, modified painting canvas.

5. Where are you, son?, 2024.

Two paintings: (1) Acrylic and vinyl emulsion on canvas and (2) vinyl emulsion on vinyl fabric.

6. Saint Joseph, 2024.

Felt, thread, plywood.

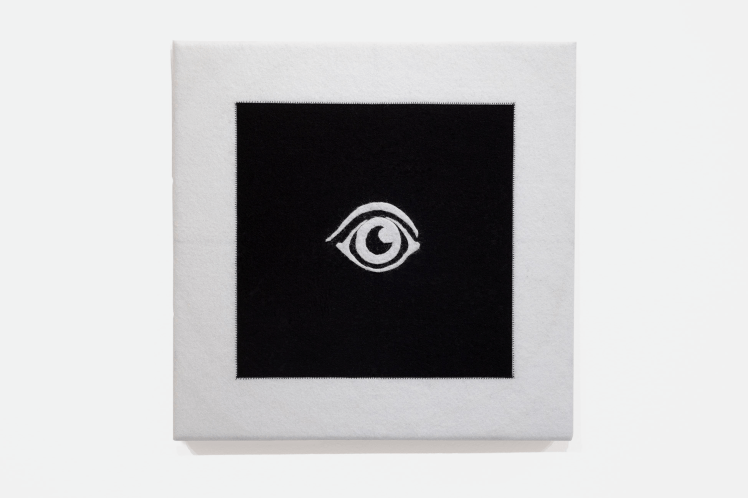

7. The Inner Eye of Thought, 2024.

Felt, thread, wooden stretcher frame.

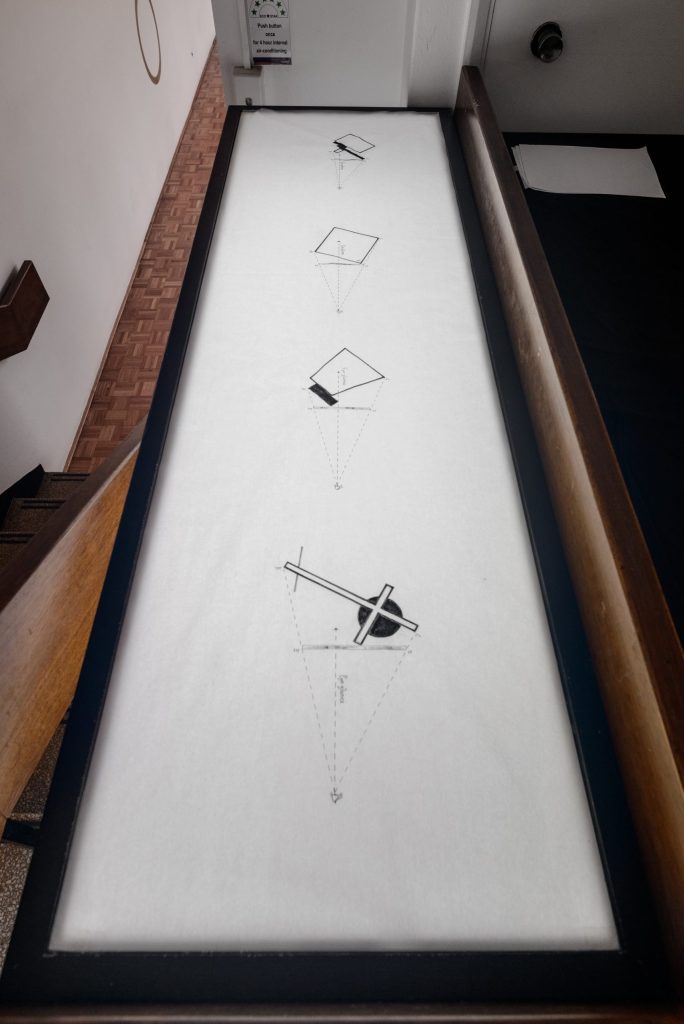

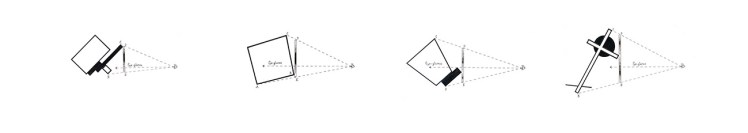

8. The Flat Characters, 2024.

Archival pen and indian ink on white tracing paper.

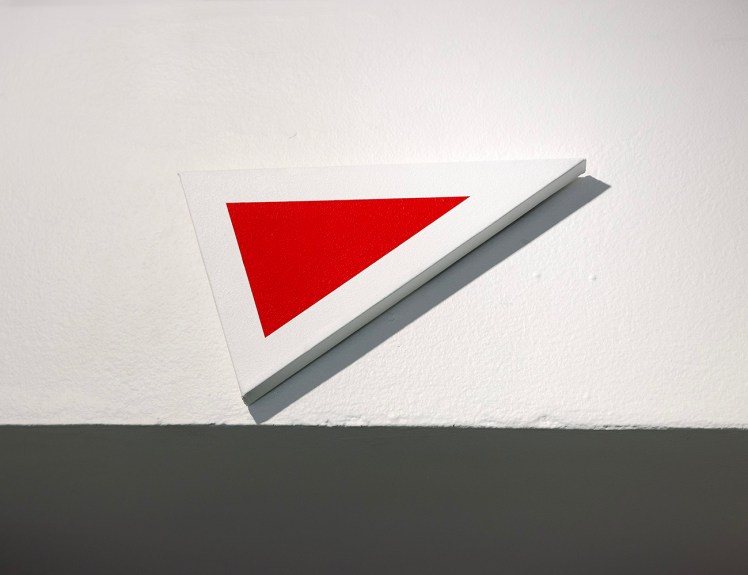

9. The Lost Isosceles, 2024.

Acrylic on shaped canvas.

10. The Irregulars, 2024.

Archival pen and indian ink on white tracing paper.

11. The Black Pentagon, 2012.

Oil on shaped canvas.

Main Gallery Area

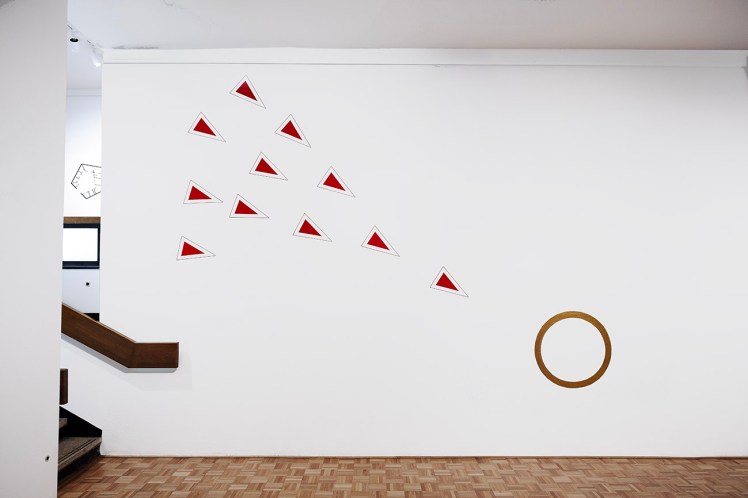

12. The Rebellion of the Isosceles, 2024.

Acrylic on wall.

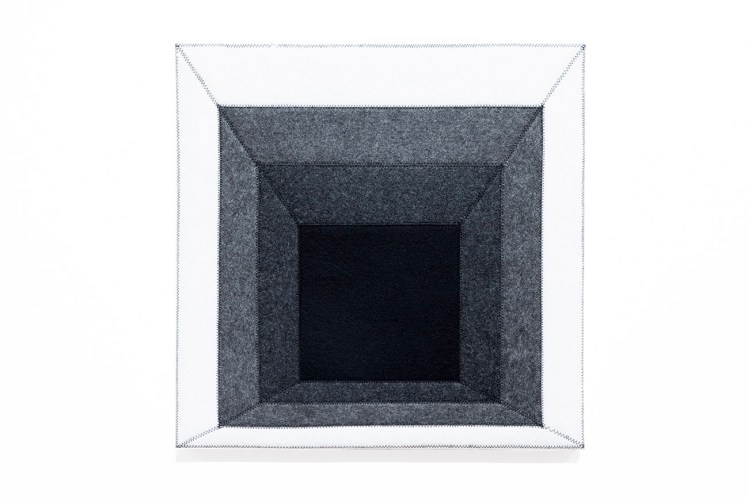

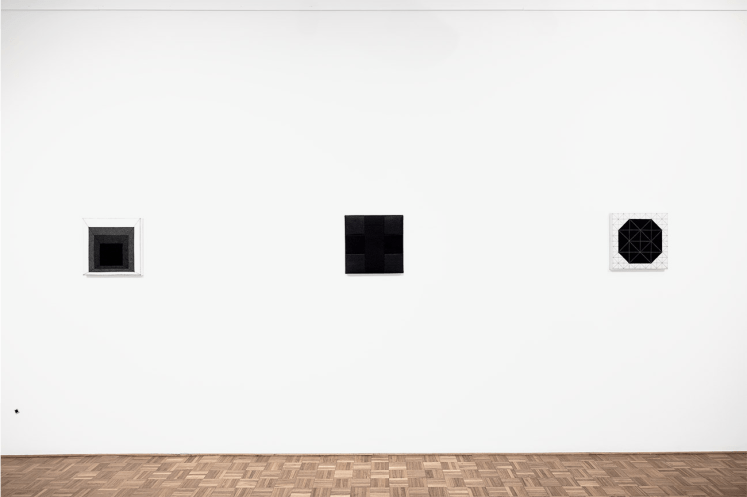

13. Homage to the Hypercube, 2024.

Felt, thread, wooden stretcher frame.

14. Untitled (‘et sic in infinitum’), 2024.

Felt, thread, wooden stretcher.

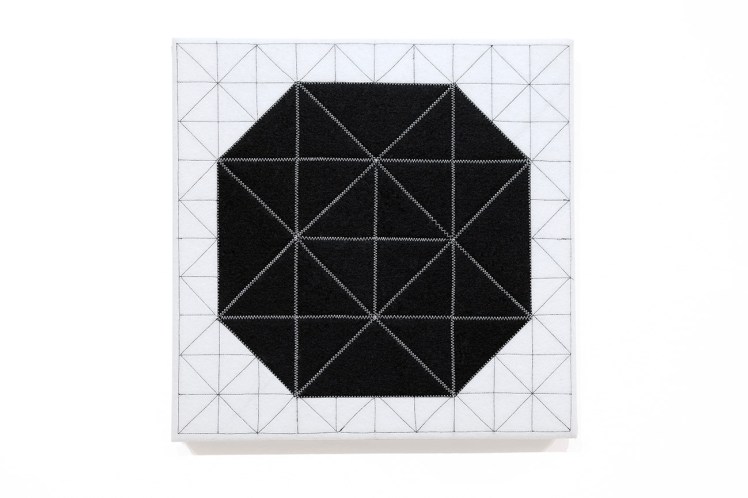

15. Counter-Composition: “The Argument from Analogy of Figures”, 2024.

Felt, thread, wooden stretcher.

16. Homage to the Pentagon, 2024.

Acrylic on shaped canvas.

17. Melencolia, 2024.

Felt, thread, plywood.

18. Chariot, 2024.

Felt, thread, plywood.

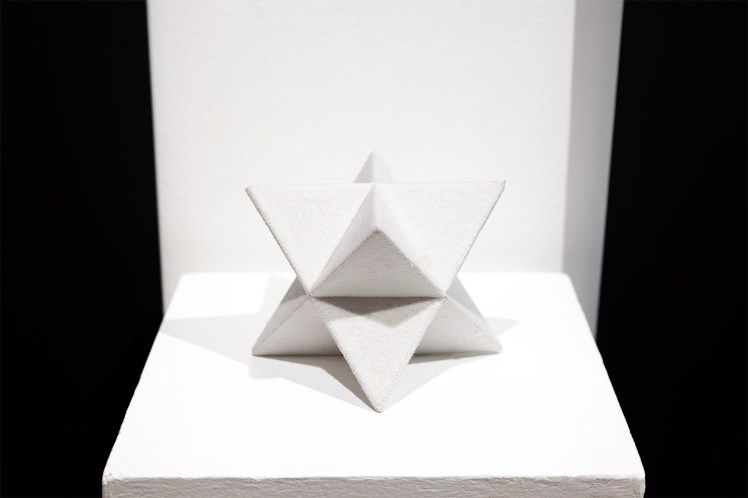

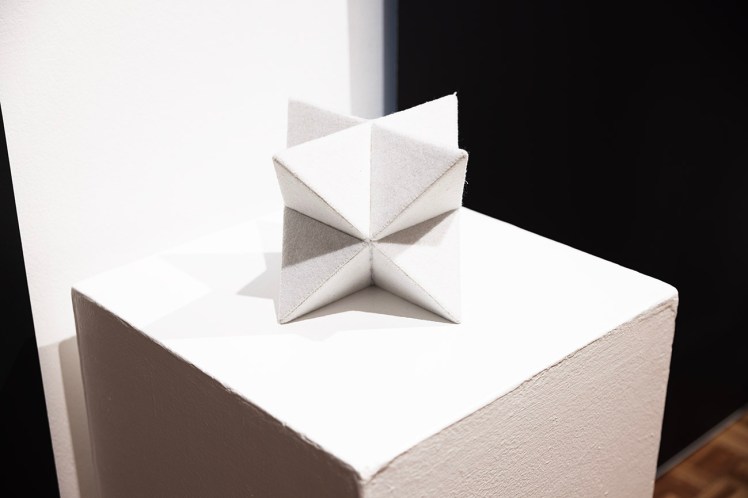

19. Hypercorpus, 2024.

Felt, thread, plywood.

20. Maze Prison, 2024.

Three paintings: Vinyl emulsion and acrylic on vinyl fabric.

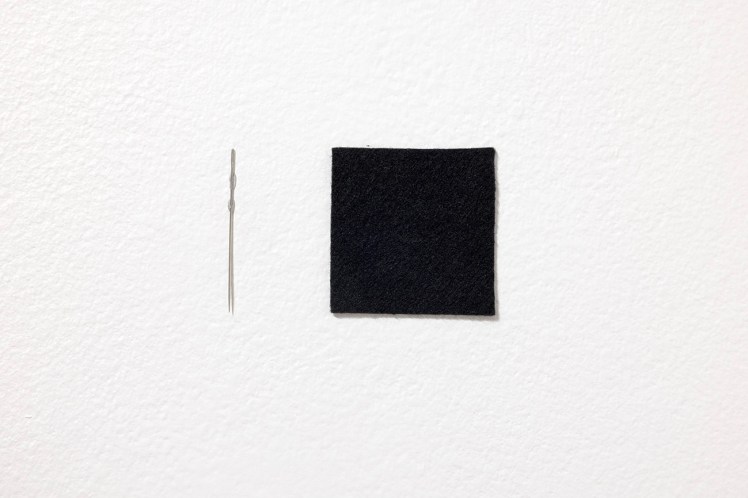

21. Mum and Dad, 2024.

Needle, felt.

Geometry, Kinship and Juxtaposition

by João Seguro

“…each geometry projects its own history in return.”1

Michel Serres

Flatness has been an omnipresent attribute in visual arts discourse since modernism. According to its main proponents, painting should develop strictly on the two-dimensional plane in order to avoid problems that would be alien to its discipline and its nature; the same should apply to other traditional artistic disciplines such as drawing and sculpture. All possible approximations between the fields of work should be avoided in order to bring Painting closer to its essence, or, as Greenberg puts it in his influential essay, to its purity.

For Greenberg, this purity was the main objective of modern painting. To achieve this goal, painting had to focus on its flatness in order to work on the formal and material properties of the medium of painting, the specificity of the métier, and commit to the absolute suppression of the mimetic characteristics that art had pursued for millennia. This essentialist vision of art defined much of what we know today as Modern Art.

It is based on the legacies and traces of the procedures of this type of modernism that we can start an itinerary through this exhibition – In the Flat Field – a joint project by artists Tom Isaacs and Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa.

Tom Isaacs and Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa are artists in whose work we can find reverberations of these modernisms, although the questions their practice pursues are often contrary to the decorum that characterises the essentialism of formalist modernism. The work of both artists is often permeated by elements that graphically refer to morphological elements of the historical avant-garde of modernism, but it is clear from the outset that what is sought, despite the direct influence, is a historical and discursive scenario that favours the construction of fictional and speculative scenarios full of critique and irony. And it is precisely through the critical nature of quotation and humour that this exhibition develops.

We can start questioning the name of the exhibition, which is an amusing tautological allusion – In the Flat Field is the title of a song and album by the fabulous rock band Bauhaus, which in turn borrowed its name from the mythical German art school, one of the paradigmatic moments in the history of modernism and the place where many of the works and theories that inform the work of the two artists were developed. What’s more, we mustn’t forget that the Bauhaus has many similarities to Vkhutemas, another very important art school that operated in Russia between 1920 and 1930, after the influence of several of the authors mentioned in Isaacs and Sousa’s work. It’s therefore a title full of wit that supports countless layers and historical intersections.

But this title, although revealing, is also accompanied by a drawing (which is the image on the exhibition invitation and the first “work” in the exhibition complex with which visitors may have had their first visual contact) that evokes another work and complexifies the network of relationships that we will come across in this exhibition. The drawing is a visual quote of the frontispiece of Edwin A. Abbott’s book Flatland: A Romance of Many Dimensions, a work that serves as the backdrop to this exhibition and the set of juxtapositions rehearsed here.

Entering the exhibition, we find a group of works where the flatness evoked by the title and context of the book intersect with the multiple dimensionalities inherited by the works and contexts of modern art.

After passing through the gallery’s green doors, we are greeted by four small works – facing us, The Inner Eye of Thought and St Joseph by Tom Isaacs, ironically underline the ocularcentric and illusory character of art, as well as its potentially redemptive quality. The iconography and materials used by Isaacs in these two pieces highlight the web of relations of affinity and intertwined lineages that assert themselves in this exhibition as a ghost inhabiting official histories.

On the heels of these pieces come two works by Rodrigues de Sousa – The Lost Isosceles and Where are you, son?, enigmatic pieces that suggest the regime of approximations between the narrative of the literary work cited and the artistic narratives from which the works of the two artists will unfold. Between the diagrams of Flatland and the modernist shaped canvases, Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa opens up a terrain of mirrored references that challenge us through the refraction of multiple dimensional beings observing each other, an allusion to a psychotic Mirror Stage where there is no time or space, because there is no present or past and geometric and spatial figures take on human features.

In Vitruvian Ghost, Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa proposes a stroboscopic projection of a square framed in a circle (a metaphor for the noblest class of beings in Flatland). The black and white of the high-speed light projection distracts us from the black square that is integrated into the circle, or is it the circle that incorporates the square? Apart from the multiple cultural references the work seems to contain, we are faced with a kind of Venn diagram that gives us another clue as to the cannibalistic regime of the exhibition project. We are at the same time inside an art gallery and at an unknown space where the creatures of the fiction narrated by A. Square dwell.

Next door, Monolith/Messenger by Tom Isaacs points out some derivations of black squares, the history of monochrome painting, painting as an object and its performativity, as if paving the way for the projection of Neo-Therapeutic Operation, a video in which the two artists collaborate in altering a square canvas (the configuration of the narrator of the story and the tutelary form of Constructivist and Modernist art), as if it were a surgical operation, sectioning it until it becomes a sixteen-sided object. This piece addresses the troubles of forced adaptation, a certain evolutionary morphology of human society that also has echoes in Abbott’s book.

Above the entrance door to the gallery, The Black Pentagon by Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa seems to be watching us. Here, Malevich’s black square is transformed into this shape and, by being placed at this spot also transforms its condition as a painting. It ceases to be a passive object for observation and suggests a renewed ontology of the observer by replicating the black of the CCTV cameras we can usually find in the corners of public buildings. The painting moves from being the place of the observed to become the intrusive place of the observer, placing the gallery visitor as an active element of the spatial device.

Flanking the flight of stairs that gives access to the second room of the exhibition there are two sets of drawings, The Flat Characters on the left and The Irregulars on the right. Remembering that in the world of Flatland there are no irregular polygons, we imagine that we are entering a world where the regular figures of Abbott’s parody are perverted by an extrinsic imagination that expands, or at least opens up the possibility of expanding, the world of his figures to other dimensions and sociopolitical ecosystems. Some of these irregulars resemble drawings we know well – it’s no coincidence… Still on the wall of the access staircase, two of the small figures from Father and Son by Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa, which will be replicated on other places later on, refer to the piece in the first room Where are you, son?; the father continues to circulate through the spectator’s space in search of his son, making this piece a kind of performative painting that circulates and makes us circulate through the exhibition space in search of its limits and its conclusion.

Curiously, going down the stairs on the right, a new black square by Tom Isaacs entitled Mum and Dad switches things up, the contrast between a sewing needle and the black fabric of the painting being decisive, as if to suggest a duality and/or complementarity and introducing a variant of kinship (personal or figurative?) that intersects with the fictional kinship of the characters in Flatland. This piece, like the other two adjacent pieces by the author, made of fabric, and with enigmatic titles such as Homage to the Hypercube and Counter-Composition: The Argument from Analogy offer a commentary on the rigid structures of modernism, their geometric and fixed modularity, although in these the spatial elements, movement and the dimension of uncertainty are some of the keys for the interrogation. The same seems to be true of Nuno Rodrigues de Sousa’s mural The Rebellion of the Isosceles. In this piece, the artist once again fuses the universes of modernist artistic practices and the geometric shapes found in Flatland, red triangular figures orientated towards a circle, or, thinking in our complex of equivalences – soldiers – towards a tutelary figure, the highest in the system of Flatland, represented by the circle. If we look at this piece away from that system, we can think of a lot of post-war French painting, the escape from structures, the metamorphosis of forms, the play of form/figure/background, typical of the proposals of the Supports/Surfaces group.

The other works in this gallery add to this game of juxtapositions and enigmas – three sculptures by Tom Isaacs on plinths advance three-dimensional geometric structures – a black cube titled Melencolia seems to play with the three-dimensionalisation of a square while surreptitiously quoting Albrecht Dürer’s piece of the same name; the plinth in turn is invaded by two pieces (Father and Son) by Rodrigues de Sousa, further increasing the scheme of tensions and intersecting spatial regimes. The other two pieces are Chariot and Hypercorpus, both of which indicate the spatiality and temporality of objects as a disruptive historical complementarity of modernity.

To conclude the exercise of going through and interacting with the objects in this exhibition and the kaleidoscopic radicality of this superimposition of images and objects, another shaped canvas, Homage to the Pentagon, by Rodrigues de Sousa, makes the figure of the pentagon reappear, omnipresent in various configurations throughout the space. This wall piece mirrors another pentagon on the floor, on the other side of the room, Maze Prison. As the name suggests, it’s a labyrinth, where other small pentagons and squares try to find their way out.

These shapes take us back to the beginning of the exhibition and to the multiple self-referentialities and extra-territorialities that are possible to find. Squares that aren’t just what they are, pentagons that aren’t what they seem to be, circles with second and third intentions (or dimensions), lost figures, others that fit in, or even some that run away, still others trying to find their way out, or forced to be what they are not.

João Seguro

1. Serres, Michel; The universal and the differences in Geometry – The Third Book of Foundations, Bloomsbury Academic, London and New York, 2017, p. XVI.